| |||

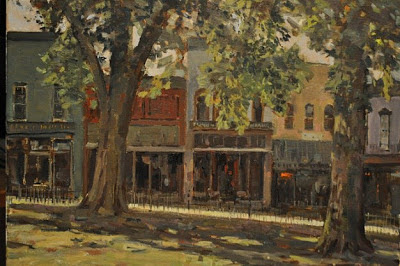

| Demo painting from the Canton Mississippi workshop |

Well here I am again, it's been a while! I have been traveling all over the country teaching workshops since last I posted. I went on tour, like a rock band. I have been in the White Mountains, Minnesota, Newburgh, New York and Mississippi and God knows where else. I can't even remember all of the places I have been. Most were three day gigs, but some were five days. I met a lot of students and had a lot of fun. I like doing workshops, and I love meeting the students. The workshop scene seems to select for an enjoyable group of participants. I run twelve hour days in my workshops, so I eat dinner and often breakfast with the students besides painting with them all day.

I think I will write about what I have seen out there. There seem to be common problems that many students have, and recently I have been aware of how most of the students have the same things to learn. I get a broad range of students in terms of ability and experience, from beginners to demi-professional, so some of them don't have these shortcomings. Most of them do. Remember, I am not talking about you, or anyone you know, I am talking about those "other" people who are far away. The common problems are these: (let me chamber a few bullets here)

- Failure to express the full range of values in the scene before them. Most of the students seem to paint in a few middle tones. I always seem to be telling them, "when you look out there, you see a dark and paint it a dark value. When I look out there, I see a dark and ask myself, which dark is it? I have several to choose from." The students use a single generic dark and a single generic middle tone, etc. They command too few values to explain that at which they are looking. I have been telling them this ;:" Did you learn to read from the Dick and Jane books? " (for you younger readers, Dick and Jane were drab children who said things like "look Jane! see Spot run! Run,run run. See Dick run!!" Spot was a dog. Dick was once a common male name. Jane was a girl's name then, much like Krystle or Brittney might be today). he teacher went up to the blackboard and wrote a list of about ten words on the board before she even handed out the book. You had to know about ten words to read even this simple story. The authors of this sorry tome couldn't tell even its banal story without at least ten words. They couldn't write the book with only say... five words, they needed at least ten. If you imagine your value scale to be words you will need about 10 or at least six or seven anyway, to tell the story that is in front of you in the landscape. You students don't have enough words (i.e. values) to tell the story of the landscape in front of you. I suspect that the best cure for this problem would be cast drawing under the eye of a master, but that is atelier training and most people just can't leave their real life behind and do that. I am trying to come up with a systematic approach to curing this problem, I do have an idea. I will get back to you on that.

- Inadequate paints and equipment. I see lots of mangled brushes, I pick them up and say "this was once a brush!" I will often see a student with two dozen brushes, none of which is in usable condition. They are as stiff as tongue depressors and worn into a point. I see a lot of hues too. Those are colors made for the student market that pretend to be the pigment but are not. Some cheaper pigment has been substituted for the necessary color. Usually this substitute is pthalocyanine plus some other pigment. I have seen a student with a pthalo pretending to be their ultramarine, their viridian and their cobalt, all on one palette. Half of their colors are really just one pigment, pthalo. I have seen whites with the consistency of joint compound and faux "cadmiums" no more powerful than fruit juice.These students have defeated themselves before they even touch their shattered, frizzled bristles to the paint on their palettes. I also see easels that wobble every time the student makes a stroke on the canvas, weird contraptions made of balsa and recycled aluminum that rock from side to side in the slightest breeze.They look like they were manufactured by someone who had heard of easels but had never actually seen one. A decent easel is going to cost more than a toaster at WalMart, that's just a fact of life. Pharaoh taught the Israelites you cannot make bricks without straw.

- Bargain canvas. I have seen students working on hyper absorbent canvas that sucks the life out of their paint. It is like painting on a loofah. The brush, instead of gliding sweetly over the canvas, scratches along like it is painting on sandpaper. You can buy a prestretched canvas at Michael's or Hobby Lobby for three dollars, but you shouldn't. If the gas it took you to drive to the store in your 25,000 dollar automobile cost more than the canvas you bought, you ought to walk there and get something that will actually work.

- A lack of knowledge of the history of painting. Students are constantly telling me about the artists they have read about in American Artist or some other magazine. Most of the time I have never even heard of these artists and when I see their work I am disappointed. I tell workshop participants that I never look to living artists as my models. These students know only contemporary painters, many of indifferent ability. To make good paintings it is necessary to know what the great artists of the past have done. If you told me you were learning to play guitar and I asked you what you thought of Chuck Berry and you answered "who?" I wouldn't think you were going to get very far.The great artists of the past dwarf ALL living artists. I know of no contemporary artist who is the equal of a Rembrandt or Rubens. It is absolutely essential to get up on the shoulders of the dead to see beyond the ordinariness of the art of our own time. Very few artists today could have cut it in the nineteenth century. We do a great job with technology and plumbing today, but our ancestors painted better. If you want to paint well read the classic texts and have giants for your heroes.

27 comments:

Awesome post! Love learning and working on seeing values and can't wait to see what you come up with. Good to start my day with your words this morning!

Smiling over this post and going to check my brushes.Delighted you are back and looking forward to more after your nap.

Please help my confusion on values. I have read and been taught to not use the full spectrum of values because it weakens the painting. Their instruction has been to narrow your values to three no more than four value groups by compressing the values together. By doing this you make a stronger pattern of shapes that holds together, especially from a distance. Please clarify. Looking forward to your response.

Re point 4 - three words: Antonio. Lopez. Garcia.

Stape, good to see you back. Loved your comment about shattered brushes. I run into this all the time with my own students. Surely the Art Devil is whispering in their ears " oh go ahead, this old brush is still good enough to use a little longer..."

Also, you are more brave than I. I'm just too chicken to come out and say in public the 19th century painters were better than we are today. It's pretty much true. (of course all the truly dreadful 19th century works probably got used for firewood during one of their colder winters).

Today's art students in art schools and universities are asked to be familiar with drawing, painting, fiber art, installation works,video, performance, and

half a dozen various digital programs. Even the sharpest of them have their poor heads spinning. They'll survive all the confusion, but I fear it is aging them prematurely.

I thought for sure your next post would be about the Inness discovery - http://www.mysanantonio.com/news/texas/article/Early-Inness-work-uncovered-at-Dallas-art-museum-3984333.php

Regarding Deborah's comment above, compressing values is something that's stuck in my head too. I've studied that luminosity and sense of light can be achieved by not going too dark or too light for the plein air painter.I guess the Impressionists worked this way, and I've been trying to understand this.

As one of your MN workshop students, your teaching opened my mind up to new questions, but not yet the answers, at my level. But it was a good foothold nonetheless.

Yeah, the value banding/compression is an unanswered problem, but anyway, please more, more, more!!!

(and I laughed a lot :) )

Amen, Stape!

Judy, the Impressionists relied on more things than just compressing their value range. They consciously placed opposite hues against each other to stimulate the eye, often to the point of putting color in where it wasn't present. (Referred to as Simultaneous Contrast of Hue) The combination of the two or more hues created a vibration which made everything appear more intense.

They were painting the optical effects of light rather than a naturalistic expression of it. A dividing line in the late 19th world of art.

The compression of values is an issue of style, mannerism, interpretation and aesthetics ( See Fairfeild Porter's work) . It is not just an issue of learning or training.

One must see all the values, learn to express them and make ones own artistic decisions. You, as the painter, decides what makes your painting as you want it to be seen.....full range of values or compressed values or flat values ( Cezanne) .

In a workshop, as a student, your job should be to learn what is being imparted to you by the instructor in that moment. After the workshop, as a mature independent painter, you use what you want from what you have learnt.

Interesting post. Some current artists who teach, recommend breaking things down to 3-5 value shapes.No wonder that doesn't work very well. But I'm more interested in the point about canvas. I make a lot of my own because I don't like the thinnness of the commercially prepared canvasses.I usually apply 3 or 4 layers of acrylic gesso to a heavier than average canvas sanding lightly between each layer. The finished product still comes out rough as sandpaper. I'm afraid to use my favorite brushes on the first layer of paint.What is the fix for this and who makes a good commercially prepared canvas? Thanks!

Marian makes an excellent comment about the topic of values. As a workshop teacher we need to state to our potential students whether they are going to be given the basic skill sets without teaching mannerisms, style, interpretation, and aesthetics. The flip side to the above statement is most excellent painters who teach also teach from a particular "school of thought." With that comes their process and how to see color and use it to name just two ideas. Again thanks for this discussion and thank you Stapleton for your informative post. Looking forward to more.

Glad you're back sharing with us, Stape! Lucky people who have been in your workshops!

I have thought about your message and I know you are such a Nice Guy that you wouldn't say anything too negative to students who buy the CHEAPEST art supplies they can find at the Dollar Store or wherever because they may not "like" it. So, let's say they take a cooking class and the chef says, "Go buy the cheapest set of knives and utensils you can find. Bring in the cheapest cut of meat you can find. And I will teach you how to prepare a gourmet meal." Yeah, right! Of course I know you could produce a masterpiece with anything, but it does make it difficult to work with students who have worn and cheap supplies. Paint On!

Theresa, it seems odd that after 4 or 5 layers of acrylic gesso, and all that sanding, you are still ending up with an abrasive surface. Perhaps the sandpaper grit is too coarse or the canvas has an abnormally large weave. Couldn't say without seeing it.

Or simply changing your acrylic gesso will help. Golden makes a good product. There are others as well.

If you want a smooth surface either use linen instead or lightly sand a wooden panel before priming it.

Keep in mind, however, that the oil film you are making not only creates a bond with the gesso through a slight absorption, there should be a mechanical bond to the gesso as well, which requires some tooth in the primer.

If you are scumbling a lot that will wear your brushes out faster as well.

Thomas Kitts

Hello Stape! I enjoyed everything about this witty article you wrote. I know you are right about those painters of the past that they are one of those many ways that an art student can learn from. Here in my country its so rare to find good books about art and I have not known of someone who has a great skills especially in realism offering workshops, unlike in America. Most university here in Philippines don't teach realism and its like I am in a wrong pond. I learned from reading generous art bloggers blogs and collecting images of the great masters of the past and there I keep on looking hoping to catch some brilliant knowledge.

Thanks Thomas. I'm using only 3 layers of gesso and a fourth only if it's needed. The canvas is on the heavy side but the weave is tight.I've used both Golden and the better quality Utrecht gesso. The sandpaper is 600 grit.I'm sure the adhesion is great but the drag is terrible.

One way to get a better hand at values is to mix up 9 or 10 gray scale values that are evenly spaced.

I use a Munsell gray scale booklet to help with this myself. Then go out and paint a few value studies.

There are a few good books out there to help, Carlson's and Payne's are the best. Carson's is better for the overall mechanics of painting outside.

I use to copy masterworks in gray scales or grisailles or make charcoal value studies of Constable's and Hudson River painters from black and white reproductions. The older books are better in this regard.

These were not intense copies more akin to poster studies to figure out how these masters designed their paintings and how the value relationships worked.

Outstanding. Glad you're back, Stapleton. All your blog postings are worthwhile.

I certainly found the Hibbard exhibit in Rockport -- and your commentary of the paintings during your gallery talk -- to be an excellent way to learn from a great artist of the past. I am still looking at the book images of Hibbard's paintings and trying to figure out how he used that diagonal perspective. It is brilliant! A knowledge of the past is essential.

Okay Theresa, tell me about the paint you are using then. This sounding very curious to me.

Thomas

Thomaskitts.com

Thomaskitts.blogspot.com

Great to read your post again and I have to agree with your comment about 19th century painters.

Thomas, it's curious to me too why the canvas turns out so stiff and scratchy. My paints are good. I look for paint that's just pigment and binder with no fillers. so, I have a combo of utrecht,gamblin,maimeri and williamsburg and a few grumbacher and windsor newton just because that's all that's available locally.Within these companies, I don't use their student lines.

I use five value families for my own work and teach this to my students. I am not leaving out the multiple values. I am organizing them into five groups to make it easier for myself to understand instead of the long value scale. They are the same values, reorganized, not left out.

Linda Blondheim

Claudio Bravo. Unfortunately, he is now (recently) among those past.

Post a Comment