Joseph DeCamp, September afternoon

image artrenewal.org.

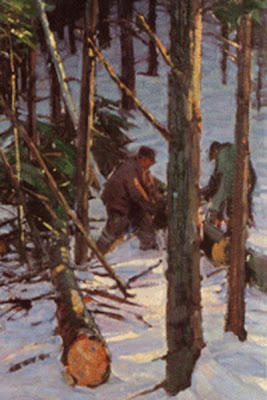

I received several questions over the course of the day about brushstroke and so I will answer those tonight. Questions are in red, my answers are in black.

1) One thing I was wondering about, maybe you could talk about is...You look to nature to get your impression, look up, mix paint, match value and color, double check and fix it. But when you've shifted the value key in your painting to whatever you're working in, say a very low key, won't the value you want on your paper be different from what you see. So is it all relational, when you stress double checking that one note, it's checking it against your interpretation and rearrangement of the value scheme you see in nature and not necessarily against just what you see? So is there any process or technique to 'shifting' from what you see to what you want to express in your painting.

For most of you , you will be painting the scene in the key it appears to you. I mentioned in an earlier post that I paint in a lowered key. I am automatically transposing the picture in somewhat the same way that a pianist might read a piece of music and play it in a lower key. Because I do it so often I might as well see it that way. I drop it into the lower key without even really having to think about it. So when I look up to double check I see the note and say to myself, I represent that with this. Its a system of correspondence.

If I drop all of the notes the same amount and they all stay in the same relationship to each other. I can still be true to the actual value relationships of nature. In practice though I often put in the highest lights up in the higher key. That gives me a look of light breaking through the painting.

There is no reason for you to start doing this. It is a personal way of doing things and you want to learn the broader knowledge from me rather than how I personally have modified the ideas in my own work.You don't want to take on my stylistic idiosyncrasy.

All sort of possibilities come from making decisions on how the painting should look rather than mindlessly transforming yourself into a meat camera. Decision making makes painting complicated, changing subjects paintable. Even just simplification requires decision making. You have to OBSERVE, THINK, AND THEN DECIDE.

2) When painting outside and you lock in your values and colors first then as the light changes I'd imagine it gets quite hard to not be caught up in what you're seeing. How do you go about relating it all back to what you had seen? There's the skill that isn't learned in the studio, how to deal with the changing light. I don't follow it throughout the day. I plot my lights and shadows and pretty much leave them alone. The trick here is to make a a picture, rather than transcribing nature. You can decide how the picture should look, and stand by that. You can't decide how nature should look and stand by that, as it is always changing. The trick then, is not to be copying nature to that great an extent, think of what YOUR picture should look like.

Joseph Decamp

image artrenewal.org.This is a fabulous head. Frank Ordaz is doing a series of posts on painting heads in his blog.. There are some valuable tips in today's post over there and I am sure his subsequent posts will be excellent as well. You can click on the link, Being Frank in my side bar and you will magically be transported all the way across the nation to sunny California.

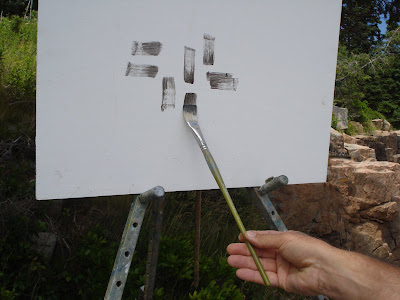

3) I wonder if you could tell us occasions when these numbered types of brushstrokes should be used---when such brushstrokes are favored by you for example, to achieve a desired effect?There are two paintings on this post. Both are by the same artist. The lovely portrait of Sally is painted in a more smoothed out refined manner. It does still has brushstrokes in it but they are adapted to the painting of a young girls face. The picture of the early autumn trees is painted in a bold sort of stroke that you probably wouldn't choose for a delicate portrait. I like to paint leaves in little rice like brushstrokes. I like to carve the contours of the earth with larger strokes perhaps from a #4 bristle. I like to paint snow in large planes and pull them together when they are all wet, to do that I like a # 8 or 10.

For clouds and skies I like big flats like a 10 or 12. I can get a bunch of different strokes out of the same brush depending on how I push its blade into my canvas. I can draw with the tip turned sideways or make a broad "slab" by using the flat of the brush.

I like to make sort of lifting, upward curving stroke for fine clouds. I use a #1 flat to paint the branches of trees, where they get finer I use a rigger, when the tips of bare branches blur against the sky I use a #4 to get that. Years of experimentation have made it so I use a number of different strokes to get the look of things out there. If there is one rule to remember though it is this;

DO EVERYTHING WITH THE LARGEST POSSIBLE BRUSH.That will give you a facile look and make your brushwork look bold and more expressive.

4) I like visible brush strokes for the most part. But having a soft edge on a nice juicy brush stroke is very tricky. If you soften the edge with a finger or another brush, it ruins the boldness!Is there a good way to get a compromise?Well there is a trade off there. With practice you should be able to soften a brush stroke a little with a bristle brush without ruining the bold look of it. Some times you can soften just one side or one end of a stroke. It may be that you will decide to leave them hard. But that can be dangerous. Many times I have had a passage that I just couldn't seem to get the way I wanted it , I softened it up and viola. it worked. Hard edges can get you in trouble, a lot more often than soft edges. For most learning painters hard edges are already a problem for them. I suggest you soften the whole thing up, and then selectively restrike some important strokes and leave those hard.

Your brushwork is like your handwriting. If you do a lot of painting it will automatically develop as you find how YOU like to do things. I wouldn't worry overmuch about developing a style of brushwork. That will just happen in time. Do try to use your brushwork in the most descriptive way you can and stay away from the little brushes. Particularly riggers. They will give you riggermortis. Also hold those brushes by the part of the handle opposite the part with the hair on it. That long handle is there to give you power through leverage. Just like on a shovel. Dont hold it way up by the ferule like a pencil. This is important . Don't choke up on that brush handle, it will ruin your brushwork. You want to swing the brush with your arm not your fingers.

I am going to return to the subject of brushwork, using a different approach in some posts yet to come. So you will hear more about these ideas down the road.

The next few posts are going to be on a number of small ideas that will only take a single post to express. I hope.