Goodbye, Liz Taylor

Goodbye, Liz TaylorI received more comments including the following;

Rubysboy said...

This post sows confusion. if the halftones are everything that's neither a shadow nor a highlight, what, then, are the lights? the lights is a term normally used to refer to all the lights as distinct from all the shadows and the lights are normally thought to include highlights, average light, and half tones, where half tones are the darkest lights. Is there a good reason confuse readers by ignoring common usage?

Dear Rubysboy;

There would seem no reason indeed, to confuse readers by ignoring common usage. And the usage I usaged was common in the milieu in which I was trained, where all the modeling was referred to as halftones, probably as a convenience. But, tonight I will present a non spheroid form and cut the demarcation into finer pieces. I don't understand how there can be average light on a sphere, as it constantly turns away from the light. Could you please link to your art on your profile? When I clicked on it I found nothing, no name, no website, nothing. If you want to post a strong disagreement with me, that is fine, but I would prefer you not do so anonymously. Keeps everything a little more civil too. I Googled Rubysboy and all I found was a Pomeranian puppy by that name for sale. Probably bites.

Brady said: A highlight is the brightest spot in the painting or drawing.

A halftone is any value between the highlight, and the bedbug line.

So, there could be any number of halftone values from 1 up to the limits of human vision. (Which I think is about 100 steps.)

So lets say that your bed bug line is value 99 on a 100 value scale and that the highlight is value 1.

(Given a scale where black is 100 and white is 1.)

This means that you could have up to 98 values in the halftones. Since all of those values are between the highlight and the bedbug line, they are all halftones.

To put what I said into context with Stape's post you can put all values into two categories.

Highlights + halftones = Lights

Bedbug line + Reflected light = Shadows.

Brady;

Yes that is what I meant. However I was speaking in the simplest form and there is another tighter definition I will now explain.

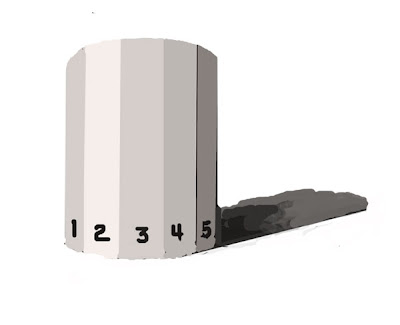

Tonight we are going to look at a more complex form and take this out a little further. Please meet me again below this crude drawing below

Last night we talked about a spherical shape. Here is a cabochon or a tetrahedral or whatever the proper name for such an object might be. It is faceted, or planar. As you read above, I have referred to all the modeling as halftones, but there are systems for dividing it more finely. In the tightest definition a halftone is exactly that,

Last night we talked about a spherical shape. Here is a cabochon or a tetrahedral or whatever the proper name for such an object might be. It is faceted, or planar. As you read above, I have referred to all the modeling as halftones, but there are systems for dividing it more finely. In the tightest definition a halftone is exactly that,the tone exactly halfway in value between the lights and the shadow.

On a sphere that would be a band about a micron wide running close to the shadow edge. but on a faceted surface it is defineable. On the form above #2 would be the highlight and #4 would (approximately) represent the halftone. The problem with this strict definition is, in use it precludes any discussion of this halftone being varied from that halftone. There is only one value that is a halftone. There are no halftones, only the halftone. That is clumsy from a teaching standpoint.

There are painting systems that premix a standard color for the highlight, average light, halftone and the shadow and reflected light. In the form above the #1 and #3 would represent the average light.

Portrait painters are very fond of these systems. I sometimes use a system like this for laying in a figure painting. But I generally discard it and go with close observation of the values after my lay in. These systems are useless training before a cast, for instance, when the point is to observe the nuances of modeling rather than large and approximate groupings of the values into two or three standard deviations. It is a good way to roughly build a structure of form, but disallows both the observation from nature of values and the nuanced infinitesimal gradations of value found in something like that Bouguereau I discussed the other night.

Now I suppose I have really sown confusion.